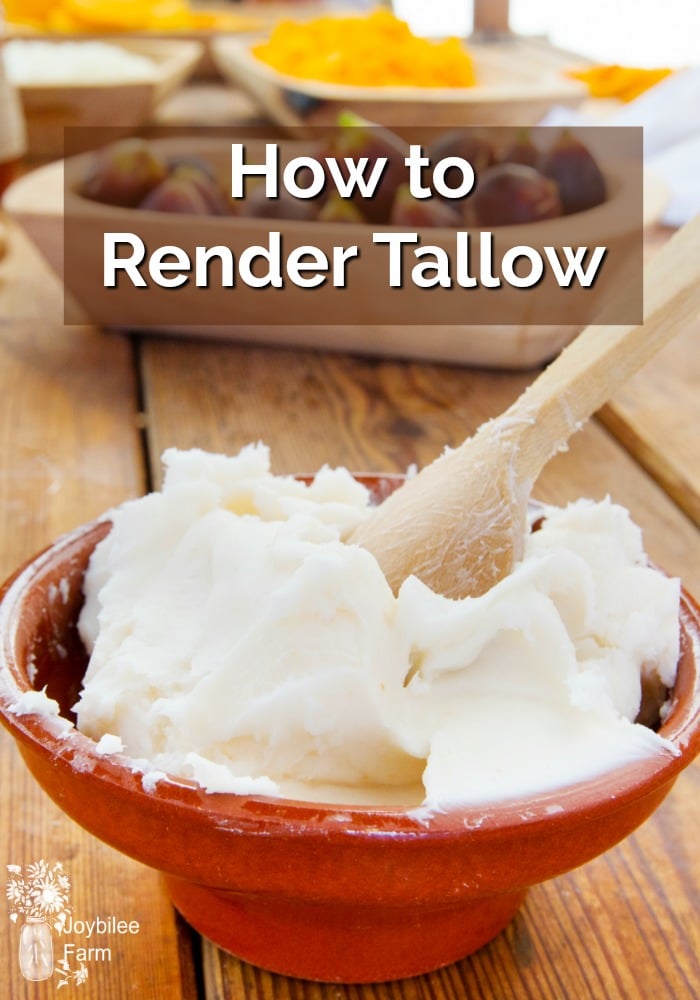

Use this simple guide to render fat into tallow and master this important homestead survival skill. Tallow can be used in soap making, for bird feeding, fire starter, and more. Depending on the fat source, this same technique can be used to render lard.

Knowing how to render fat into tallow is an important homestead survival skill. Rendered fats can be used for soap making, cooking, baking, conditioning leather, candle making, and as fire starter. Rendered fats are stable, safe for storage, and won’t go bad if kept in cool or cold storage.

Different Animal Fats

Animal fat is a valuable substance. In commercial meat processing, animal fat is sent to a rendering plant to be rendered into animal feed. On the homestead, you can render fat on your kitchen stove or better yet on the wood-stove (free heat source). Beware that rendering fat will fill the house with the smell of roasting meat, some find the smell nauseating. So if you are sensitive to smells you may want to do this in an outdoor kitchen.

Fat from goats, sheep, llamas, alpacas, deer, moose, elk, caribou and other ungulates is hard and when rendered is called tallow. Fat from pigs, bear, and rabbit is soft fat, and when rendered is called lard. Fat from poultry such as duck, geese, and chickens is called “schmaltz” and is soft, almost liquid, at room temperature. The fat is rendered the same way regardless of the animal that it comes from. Softer fats render faster, and fats from different animals should be rendered separately.

The harder fats make a very good soap for laundry and other household cleaning products. It can be used as a bathing soap, as well, and is a good grease cutter. However, most bathing soap these days includes coconut oil and olive oil which provide luxurious lather, as well as skin moisturizing qualities. Hard fats can also be used as suet for winter bird feeding, suet isn’t needed to feed summer birds, like hummingbirds. Softer fats are good for pastry and baking purposes.

How to render fat into tallow

Equipment:

To render fat into tallow or lard you will need:

2 Large stock pots with lids

A long handled spoon to stir the pot

Fat pieces which have been cleaned of residual organ meat. Muscle meat is all right, just keep meat to a minimum.

Small amount of water

Heat source

Procedure to render fat into tallow or lard

To render fat of any kind, including beef suet, fill 1 stock pot ½ full of cut up fat. The fat may have some meat scraps and perhaps bone attached. This is not a concern. If the fat is from the inner organs, such as around the kidneys (the highest quality fat), remove the kidneys and organ meats before rendering or the final fat will smell off.

Add enough water to cover the bottom of the pot to 1 inch. This will help transfer heat to the fat and prevent burning. Put the pot over medium heat and heat thoroughly. Stir the fat once or twice until it becomes translucent, to keep it from sticking to the bottom of the pot and burning. As it continues to heat the fat will become liquid and the chunks will shrink. The liquid in the pot will begin to bubble and the water will evaporate. Continue stirring occasionally to transfer the heat to all parts of the rendering fat. Once all the water is evaporated the temperature will rise. At this point you can remove any bones that made it into the pot, with your long handled spoon, and put them aside for another purpose.

As the fat begins to render, you can add more pieces of fat to the pot. However, don’t fill the pot more than 3/4s full. As it heats the fat will expand and you don’t want the hot fat to boil over onto your stove, or other heat source.

Caution:

Fat is flammable and boiling fat can smoke and catch fire. At this point, in rendering, watch it for smoking. You don’t want to let the pot get to the smoking point or you can have a flash fire. If you see any smoke, remove it from the heat source immediately, and cool it down before proceeding.

Never use water on an oil fire. Keep your pot lid handy, and if a fire starts, slip the lid over the pot from the edge to deprive the fire of oxygen slowly. If you slam the lid onto a flaming pot, it may not starve the fire of oxygen and it can continue burning under the lid. Turn off heat source without moving the pot, if possible, and let cool. Fat that has flared is still safe to use, just make sure the pot has cooled down enough to not re-flare before you remove the lid, or turn back on the heat source.

The pot will need to bubble gently (simmer) for several hours until all the fat has become liquid and the water in the meat has evaporated. The meat will be hard and crunchy – usually referred to as cracklings. This can take all day or even several days, depending on how big your stock pot is.

Remember, don’t leave the pot unattended on the heat source. I will remove the pot overnight and resume the heating in the morning if necessary.

Clarifying the fat for clean tallow

Place pot on heat source and bring to a boil until the whole pot is liquid. Remove from heat and allow to cook completely. The fat at the top of the pot will harden and can be lifted out in a solid piece. The bottom will be covered in a wet, grey slimy sludge. Scrape or cut this off and feed it to you poultry. It’s the coagulated blood from the rendering process, and it is full of protein. The clean white fat is your finished tallow. I like to melt it one more time and then pour it into wide mouth canning jars, or other storage containers. Cover jars with the 2 piece lids and store without processing. These do not need to be sealed. All water is removed during the boiling process and the tallow is clean of impurities.

Your finished tallow can be used as you would lard, although it will be a bit harder than lard for pastry baking. It can also be used to make soap. Candles can be made with hard tallow or a combination of tallow and bees wax. Pine cones dipped in tallow and then allowed to harden, make easy fire starters. Rendered tallow can be used for bird food to feed insect eating birds like woodpeckers and flickers.

At our house the chick-a-dees will perch on the kitchen window to get our attention when the suet feeder is empty. Once we fill it they come back one more time to say, “Thank you”.

Your Turn:

What animal fat(s) have you rendered? How have you used tallow, suet, or lard? Leave a comment.

I rendered pork fat from some pork shoulder I’d trimmed and cubed for canning this week. I made mention of the process in my “What We Spent” post today, and have provided a link to these instructions. I’m sure my readers will find them very helpful. Thank you.

Sorry for the confusion, Sandra. I’ll try again.

1. Put the fat scraps in a pot with a bit of water. Boil it. The water will evaporate. Once that happens the fat increases in temperature and starts to bubble. At this point the liquid fat melts out of the scraps. The meat and blood portions of the scraps will crisp up and this is the cracklings. The fat is held together with fibers. Depending on which kind of fat you are rendering — it will melt at different rates. Fat around the kidneys melts very quickly and completely. Fat that was trimmed off the muscle has a slower melt rate. Its this fat that may not render out completely and may remain soft, when the other is ready to strain. (Think of the fat at the edge of a T-bone steak.)

2. As it continues to cook the fat becomes so hot that it starts to bubble up and when you stir it down it just bubbles harder. At this point remove it from the heat source or it will boil over. Most of your fat will be liquid but there will be other portions of fat that are still soft and won’t be completely rendered. This is the portion that you want to continue rendering. But this is the point that you want to strain out the liquid fat. If you continue to try to cook it down, you will be fighting with it and your good tallow will begin to smoke and burn. You don’t want it to go that far. Its better to take the liquid fat and separate the cracklings, and just put aside the fat that isn’t quite done for a second batch. (Sometimes at this point, if I don’t want to do another batch right away, I will just press this partially done fat with the back of a spoon to get out any liquid fat being held by fibers in the soft fat, and then feed it to the chickens with the cracklings, rather than render it again.)

3. Strain the liquid fat to remove the crackings. Put the still soft fat pieces to the side for further rendering in another pot. I have a stainless steel cone-shaped strainer that I use for this. The holes are small but not as fine as a wire mesh or coffee filter, so some finer bits of the crackings does get through. These will drop into the water in the clarifying stage.

4. At this point you need to clarify the liquid fat that you have just strained. Clarifying removes impurities that can cause your fat to go rancid in storage. It will also remove any grey colouring and leave your fat a creamy white to snow white colour, depending on what your animals were fed. To clarify the fat put water in a clean stock pot about 1/3rd full. Blood heat is body temperature. You can touch the vessel that the fat is in and it won’t feel hot. You want the fat to cool to blood heat so that when you pour it into the water it won’t splash up and burn you. So “blood heat” isn’t a temperature. You just don’t want it hot. You are avoiding the reaction that will happen if hot fat and cold water come in contact with each other.

5. Boil the water and fat together in the clarifying pot, for about 10 minutes. Remove it from the heat and allow it to cool naturally. If you are rendering tallow (beef, lamb, goat,) you will have hard white fat on top of the water, when it cools. If you are rendering lard, it will be softer but still floating on top of the water. Tallow can be lifted in one piece off the top of the pot, once it is cold. You will see bits of grey matter on the bottom where the tallow touches the water. Scrap this off and discard. Your tallow will be white and will keep in a cool, dark place without canning and without refrigeration for many months. I have two year old tallow in my storage that I am still feeding to the winter birds and using for soap.

I hope this makes more sense to you now. Thanks for your questions.

Chris

“Once the fat is completely liquid and the cracklings have sunk to the bottom, cool the pot to blood heat. Spoon off the liquid fat into a clean clean pot that is 1/3rd full of hot water. Strain other fat and transfer the liquid to the pot. Reserve the nonliquified pieces to continue rendering. Remove cracklings and drain in a metal sieve. Save the cracklings for the chickens or use as a garnish for salads in place of bacon bits. Add the liquid fat to the pot.” This paragraph is completely confusing to me. If the fat is comopletely liquid, as in 1st line, what am I spooning the liquid off of? And what “other” am I straining if I have spooned off all the fat? What is “blood heat”? Where are the non-liquified pieces from if I have completely liquid fat as in the first line? Then after the cracklings line, I have to add what liquid to what pot? Didn’t I add all the liquid to the pot in the 3rd line from some other fat? I really want to learn how to do this, but I’m just not grasping the proceedure. Would apprciate it if you could try to explain again.

thank you so much, I’ll give it a try!

The clarifying step removes impurities from the fat. Impurities can make it spoil or go rancid in storage. By removing them you increase the shelf life of your product, keep it smelling sweet and inhibit mold growth. Your lard will be whiter once its clarified.